Hijaab: What’s In The Head VS What’s On The Head

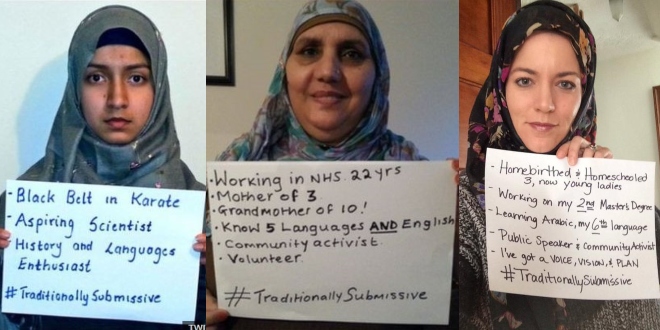

Three years ago, a viral trend under the hashtag #TraditionallySubmissive was seen across Twitter and other social media platforms with Muslim women holding placards, after the then Prime Minister, David Cameron had shared his views demeaning Muslim women in a private conversation.

Listing their achievements, Muslim women had taken to social media to prove that they were more than the hijaab they work or the values they adhered to.

While these movements are a response to the rising alt-right sentiment, here in Pakistan, Hijaabis are also trying to make a mark for themselves by proving that there is more to their lives than the garment on their head.

As someone who donned the hijaab for a decade and out of her own will, I feel that the relationship with the hijaab is a complex one and cannot be seen in black and white, especially in a country like Pakistan where one (large) section of the society approves it and the other section shames women who step out in hijaab.

It must also be seen that brands do not cater to women who wear hijaab rather only recently, some of them started including them in their campaigns, and perhaps the reason behind it would be the idea that a hijaabi is a person who can only speak about beliefs and religion, and not lifestyle or fashion.

As mentioned earlier that hijaab cannot be viewed in a vacuum. Both views regarding the act of wearing also need to be connected to the woman’s agency over her body rather than simply putting it under two labels of oppression and empowerment, because it can fall under either according to the context and placement of the person wrapping or unwrapping the garment around their body.

In fact, the trend was challenging the stereotype surrounding the hijaab and showed how there is constant conversation about women with an ease of categorizing them into different boxes. This is important to understand because if a woman covering her head is trying to make a point, it would either be taken too seriously or would be disregarded completely under the idea that such women cannot think beyond the garment on their head. A thought which needs to be revised thoroughly.

Inclusivity or tokenism?

It is also thought that some brands take a hijaabi model in their commercial to show that they are inclusive. However, bloggers feel that it is a step in the right direction because some visibility is better than none.

Blogger, Tahleel Khan, currently pursuing her education in medical, is a makeup artist and blogs about fashion and lifestyle hasn’t felt that the hijaabi women taken for campaigns are a ‘token representation’, and that she is given enough space alongside non-hijaabi women, in her own personal experience.

“I do not support the idea of stereotypes, be it for any group, and yes hijaabis are stereotyped but that has more to do with toxic societal norms than anything else. There is no doubt that there is a lot of pressure on hijaabi influencers with regards to their commentary of religion but majority of the hijaabi bloggers I follow, talk about fashion, lifestyle and makeup and they do not feel the need to drag in faith like it’s their responsibility,” she said.

Speaking about the attitude of brands and campaigns she said that she felt that they do offer a good window.

“I think it’s a step in the right direction because there is hardly any representation of women who cover their head. I won’t say I am glad with the bare minimum but I won’t dismiss the efforts which are being done,” she said.

Tahleel also lamented that underrepresentation of groups can be seen by who walks on the runway.

“Just like a black/transgender character should be played by a black/transgender person, a person who does not cover her head should not do so for a brand because a hijaabi is out there who can do the same. There are entire groups of women who wear dupatta on their heads yet we would hardly see brands catering to them, and it seems that they do not focus on their homes,” she pointed out.

She felt that this attitude was not restricted to Hijaabi women only rather any woman, who was not skinny, with long hair and fair-skinned and having unattainable features would be chosen instead of those who do not fit the bill, hence she appreciates all campaigns which do choose to steer away from the norms.

Wrapping into a stereotype

Blogger Anum Jaffry, who has been in the field for a decade now, said that while she personally did not face any such limitations, she did feel that there is a prevailing mindset that a woman who covers her head would only be devout and religious.

“There is this notion that they cannot talk about other things like fashion, lifestyle and that their views pertaining to faith would be strict, and that they would only speak about hijaab, whilst women have proven time and again that they can perform in tech, travel and many other sectors as well,” Anum said, who has been involved with blogging about tech and now focuses on parenting and social issues.

Speaking about the vitriol received by women who do not cover their heads, Anum agreed that it wasn’t unreal and that it was about the mindset.

“In our society, people would pay heed to a cleric even if he utters things which are unreasonable, and similar angle can be applied to a hijaabi as well that even if a woman covering her head would say something misleading, people would be quick to agree as compared a non-hijaabi saying something beneficial,” she said.

While brands may capitalize on all that they deem fit under inclusivity, at the end, it also comes down to the complex idea of agency of women and how the garment is used in different ways to govern women’s bodies.

For my personal understanding, I always go back to the momentous scene at the English Defence League protest in 2017 when a non-hijaabi woman, Saffiyah Khan came to the rescue of a hijaabi woman, Saira Zafar who was being harassed by the EDL members threatening to harm her, because as it is said, it is more about what is in your head rather what’s on your head.